Yes really! If you combine three buckets of concrete sand and a bucket of lime putty you will generally end up with three buckets of mortar.

Take a look at our FAQs below and see if we've already answered your question, otherwise send us your question now.

What is lime?

In the context of building, lime is basically a binder – the original ‘cement’. Lime binders are used to make mortars, plasters, renders, concretes and limewashes, having been in use for at least 10,000 years.

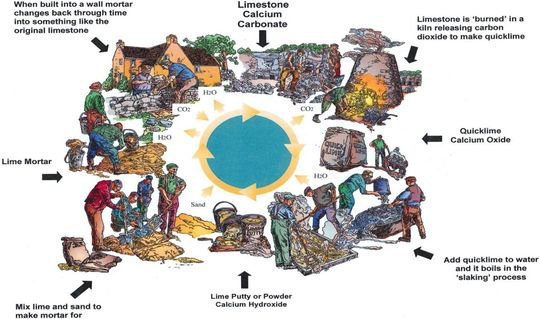

What is the lime cycle?

The lime cycle is the chemical cycle that turns a piece of raw limestone/chalk/shells into lime mortar. This is the basic non-hydraulic lime cycle:

Why should I use lime?

Lime mortars have certain characteristics which make them the most appropriate material for repairing buildings constructed or finished with lime. Lime mortars allow traditionally constructed (mass wall) buildings to ‘breathe’, unlike modern ordinary Portland cement (OPC) mortars which can be virtually impermeable to moisture, trapping it within the walls and leading to dampness and stone decay.

Why shouldn't I use cement?

We think cement is a great material, it just shouldn't be used on masonry buildings! Cement is a brittle material that doesn't allow for the movement of old buildings and therefore is prone to cracking. It is non-permeable so while it's in a good condition it stops moisture from entering a structure, however once it's cracked moisture will get in through the cracks but cannot easily leave because the evaporation surface is far too small. Cement is bad for soft (high permeabiliy) stones; instead of the mortar joints handling the moisture, the stone will, which leads to deterioration mainly through deposition of soluble salts which expand within the stones structure and also by freeze-thaw mechanisms. Cement is bad for hard (low permeability) stones; buildings of granite or basalt for example are even more dependent on 'breathable' mortar joints for allowing internal moisture to escape because it has no pathway through the stone.

Where can I get lime?

‘Builders lime’ (CL90) is available from most local builders merchants, but is generally not suitable for making lime : sand mortars. A number of specialist lime mortar suppliers exist throughout the UK and abroad. However, be aware that suppliers will have a vested interest in selling you their materials (whether appropriate or not). It’s always best to seek independent advice on the correct materials for the job – it could save you time and money! If you want to know more about how to use lime, what products to use and where they are available please contact us.

What type of lime should I use?

There are a wide range of different lime mortars available, all with different characteristics, and suitable for different applications. Non-hydraulic limes (CL90) are commonly available as ‘lime putty’, in 25kg bags or by the tonne. Natural Hydraulic Limes (NHL) Mortars are commonly available in 25kg bags from a wide range of manufacturers. NHL’s come in a range of classifications based on compressive strength in N/mm2 at 28 days: NHL 2, NHL 3.5 & NHL 5. Generally, the greater the compressive strength, the lower the vapour permeability and flexibility of the mortar. Mortars should be always be fit for their purpose, taking account of issues such as; the current performance requirements in use, ease of use, and compatibility with original historic materials.

Where can I get advice on choosing the right materials?

The Scottish Lime Centre Trust, through our Buildings Advisory Service can provide independent advice on the specification and use of lime based materials, whether for historic building conservation and repair, or for new-build projects.

Where can I get training on using lime mortars?

The Scottish Lime Centre Trust, provides a wide range of short training courses, whether you are a building contractor, a building professional, or homeowner. Longer courses, including formal qualifications are also available for industry. Further information on the range of courses available can be found by going to our Skills Training pages.

Is there an environmental benefit in choosing a lime mortar over cement?

With a growing emphasis on the need to reduce energy consumption and reduce CO2 emissions there is an argument for the use of traditional limes. The production of many natural hydraulic limes offers a significant reduction in energy, compared to that required to produce ordinary Portland cements (OPCs).

When is re-pointing required?

Re-pointing is necessary when existing mortars have weathered to reveal open or recessed joints, which are vulnerable to water penetration. Where existing, original mortar appears sound, it should be left undisturbed. Often, only patch pointing is required. It is recommended that you should have a sample of the original mortar analysed to reveal its constituents which can aid specification of a replacement mortar, and by identifying a 'matching' sand you may well be able to get a mortar of a similar appearance to the original.

Should I remove any existing cement pointing?

In most cases, yes, as cement mortars can damage adjacent masonry and can cause moisture retention within the walls. However, there may be cases where removal will cause substantial damage to the adjacent masonry – careful judgement based on the success of small trial areas should determine whether or not removal is appropriate or not, and this must be carefully considered against any existing problems with the building or structure, caused by the presence of cement pointing.

Can I do lime pointing myself, or should I employ a competent tradesperson?

We would normally advise that you employ a competent tradesperson with the appropriate experience – you should always ask for examples of previous work carried out, and satisfy yourself that they will carry out the work to your expectations. Sample panels should always be carried out for approval at the earliest date. However, we do offer a range of training courses suitable for those with minimal tool skills, and our consultants can advise on the appropriate materials and methods of repair, should you wish to carry out smaller scale works to your own property.

How do I choose a suitable mortar for pointing masonry?

Firstly, as a basic principle, the mortar should always be weaker than the surrounding masonry. Issues such as substrate type and condition, site exposure, time of year, ease of use and compatibility with existing mortars must also be considered. The choice of aggregate is also an important factor. Sharp, well graded concrete and building sands are generally used in lime mortars – for most pointing where mortar joints are 10mm or wider, a sharp concrete sand is usually appropriate.

How do I match the colour of a lime mortar?

The colour and texture of a sand has a considerable impact on the appearance of the finished mortar. The fine aggregate particles give a lime mortar its colouring; the larger fragments give its texture. Most lime binders are white, light grey or cream in colour, and therefore the colour reproduction of the sand is excellent, compared to OPC mortars. We can carry out analysis of original mortars and isolate and grade the original aggregates used to help with matching. We have a Sands & Aggregates Database with samples and information on currently available sands and aggregates currently being produced throughout the UK, allowing us in many cases to be able to recommend a suitable matching sand as part of our mortar analysis procedure.

How do I make sure I get lime pointing right first time?

The successful use of lime mortars relies heavily on the use of good quality, appropriate materials, and on adequate preparation of the wall surfaces. Curing of lime mortars is critical, and can be more onerous than that curing for cement mortars (depending on the time of year and local environment). This requires appropriate levels of wall protection following application of the mortar.

What is harling?

Harling is a thrown, or cast on finish of lime and aggregate and is the most common type of lime mortar coating in Scotland. Traditionally, lime harling was applied as a single or two coat application. Scottish harling differs from the English way of roughcasting, and from the methods adopted to apply modern cement harling, as these are commonly trowelled on undercoats followed by a cast on ‘wet dash’ (lime or cement slurry) or ‘dry dash’ (cast on dry pea gravel or grit). Lime harling provides a weather protective and decorative coating, often covering rubble stone or brick masonry.

What is render?

A render is generally a flat floated coating, which can be trowelled on, or cast and pressed back to a smooth finish. Smooth render, sometimes referred to as stucco is less common in Scotland and in vernacular building. Often, smooth renders were lined out to imitate ashlar stone masonry.

Can I carry out harling work competently without employing a experienced tradesman?

As harling is a skilled job it is not recommended that the work is carried out by an unskilled person - especially for hand cast harling. If you would like to learn more about the process however we frequently run courses on traditional harls and renders.

How long can I expect the harling coat to last?

The function of lime harling dictates that it should be less durable than the host masonry, and can in fact lengthen the life span of a building if applied and properly maintained. However, we have seen examples of lime harling which remain after hundreds of years with little maintenance – even on some ruinous buildings! The use of an appropriate specification, and a high standard of workmanship will enhance the lifespan of an external lime coating.

Will the harling require ongoing maintenance?

It is important that a planned preventative maintenance approach is taken as with all building maintenance. It is also important to be reactive to any minor defects that occur by careful patching and/ or the use application of limewash to protect the underlying harling.

What is limewash?

Limewash is probably the earliest form of paint – basically a mixture of slaked lime and water. Limewash was commonly used as a finish for harling and render, but was also used internally. Locally derived natural earth pigments were traditionally added to a limewash providing a wide range of ‘regional’ colours. Limewash is also suitable for use on walls and ceilings internally and when correctly applied is a durable material. Limewash can be made up on site from lime putty or weak hydraulic lime, or alternatively can be purchased ready made and coloured from specialist suppliers.

Why should I use a limewash?

Limewash protects underlying lime coating and masonry as it acts as a sacrificial layer. It also remains vapour permeable thus allowing moisture to evaporate from the building fabric. Most modern masonry paints have very low vapour permeability (if at all) and will trap moisture within a wall or building, leading to greater problems of internal dampness and timber rot. Modern masonry paints also tend to peel and crack, and are affected adversely by UV light, unlike limewashes.

How many coats of limewash should be applied?

It really depends on what type of limewash is being used, how exposed the building is, and how accessible it is for future maintenance. Often limewash, made from lime putty, requires around 6 coats initially, but certain types of limewash may require less. As with any paint coating, limewash will require recoating periodically to maintain its appearance and ability to protect the underling coating or masonry.

Can I limewash onto a cement based render or coating?

Limewash works best on backgrounds with a moderate to high level of suction, i.e. other lime mortars or coatings, sandstones and softer fired bricks. However limewashes with additives are available from specialist suppliers which will provide an improved bond with more difficult or low suction backgrounds. Specialist advice should always be sought with regards to their correct specification.

Why might I want to have my original mortar analysed?

Analysis of mortar samples can provide important information that can be used a starting point for the specification of repair mortars. For patch repairs where colour and/or texture matching is required, laboratory analysis can be used to isolate the (non-carbonate) aggregate and determine a closely matching sand, which will give the mortar a similar appearance, and binder which will give a similar performance to the original material.

What else can mortar analysis tell me?

With the correct interpretation, mortar analysis can be used to identify failure mechanisms of lime mortars – normally this would be carried out in association with an inspection of the building, and materials in situ. Mortar analysis can also identify the presence of particular components used within materials (e.g. cement, organic compounds and other materials which are not visible to the eye). It can also be used for investigative analysis for archaeological or research purposes.

How much does mortar analysis cost?

The cost depends on what type of analysis is required, which is determined by what information you want to know about the sample. See our mortar analysis page to find further information on the types of analysis available, please contact us to discuss the cost of analysis. When we receive a sample we will provide our initial recommendations for analysis along with costs and a likely timescale for the work. We will not carry out any chargeable work without agreeing the costs in advance with you.

If I am sending a sample by post, what size does the sample need to be?

Preferably samples should be at least 50g of bonded (rather than powdered) material, in a bag marked with the building name and location from which the sample was taken. This should be well packaged and sent along with our Sample Information Sheet and Client Details Form (available for download on the mortar analysis page), any additional background information and photographs. You can also email photos with any questions to us – all you have to send by post is the sample.

What techniques are presently available for analysis?

There are a number of techniques available at present to determine the characteristics of historic mortars- see our mortar analysis page for details. It is common to carry out analysis using two or more of these techniques which together build a clearer and more accurate characterisation of the mortar. Some commonly used techniques include; microscopy, wet chemistry, x-ray diffraction and petrographic (thin section) analysis. More detailed and in-depth procedures can also been undertaken.

Why has my lime mortar failed?

There can be many reasons for a lime mortar to fail, but common reasons include incorrect mix proportions and the mortar having not fully carbonated and therefore not gained its full strength. Mortar analysis can help to identify the potential reasons for the failure.

Is a 1:3 mortar mix (1 part lime to 3 parts sand) always suitable?

No! In many cases it may be suitable but it's important to remember that this isn't always the case. The mix proportions are based on the need to infill all of the space between sand grains with the lime binder. Sand is a very variable material and the amount of space available between the sand grains within a confined area varies based on the 'grading' of the sand. Well graded sands, like most standard concrete sands, will have grains of many sizes. In these sands the smaller grains are able to infill the spaces between the larger grains. In less well graded sands, for example building sands, there is less variation in grain size and therefore there may be more space between the grains and therefore a higher amount of binder may be needed to fill all of this space. Modern dry lime hydrate mortars are commonly mixed in proportions from 1:2 up to 1:3 depending on the sand being used.